Petroglyphs in Central Asia

Petroglyphs in Central Asia

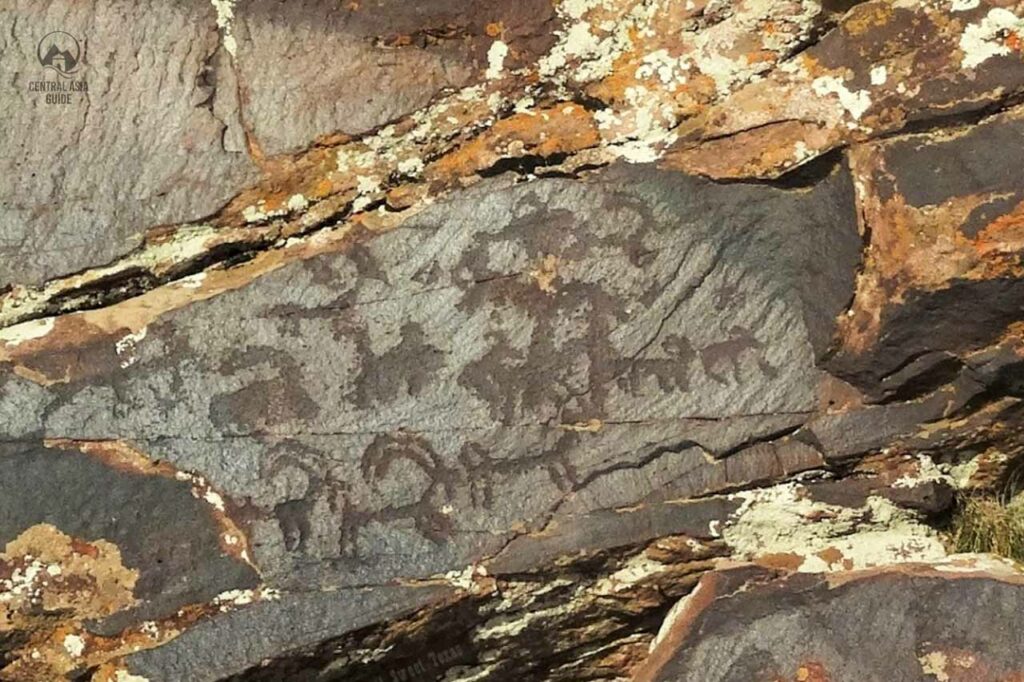

The earliest artistic manifestations in Central Asia are represented by petroglyphs, drawings made on rocks in the open air. Due to the geomorphology of Central Asia, pastures are dotted with rocks, moraines, and cliffs covered with black patina. Striking these stones with another stone or a metallic object reveals a lighter surface beneath the patina, allowing for the creation of drawings. In general it can be said that there is an enormous amount of petroglyphs in Central Asia and one can even stumble upon them by accident while walking in the nature.

In the 20th century, archaeologists became interested in the petroglyphs of Central Asia, particularly after the discovery of Saimaluu-Tash in Kyrgyzstan in 1902. In 1956, V.M. Gaponenko discovered Zhaltyrak-Tash in the Talas region of Kyrgyzstan, while Anna Maximova discovered the now-famous site of Tamgaly in Kazakhstan in 1957. New research began in the early 1970s, including the work of A.N. Maryashev in Kazakhstan, who discovered Eshkiolmes and Bayan-Zhurek, and G.A. Pomaskina, who first documented monuments around Lake Issyk Kul. Other well known major sites with petroglyphs are in Langar, Pamir, Tajikistan.

Typical Petroglyph images in Central Asia

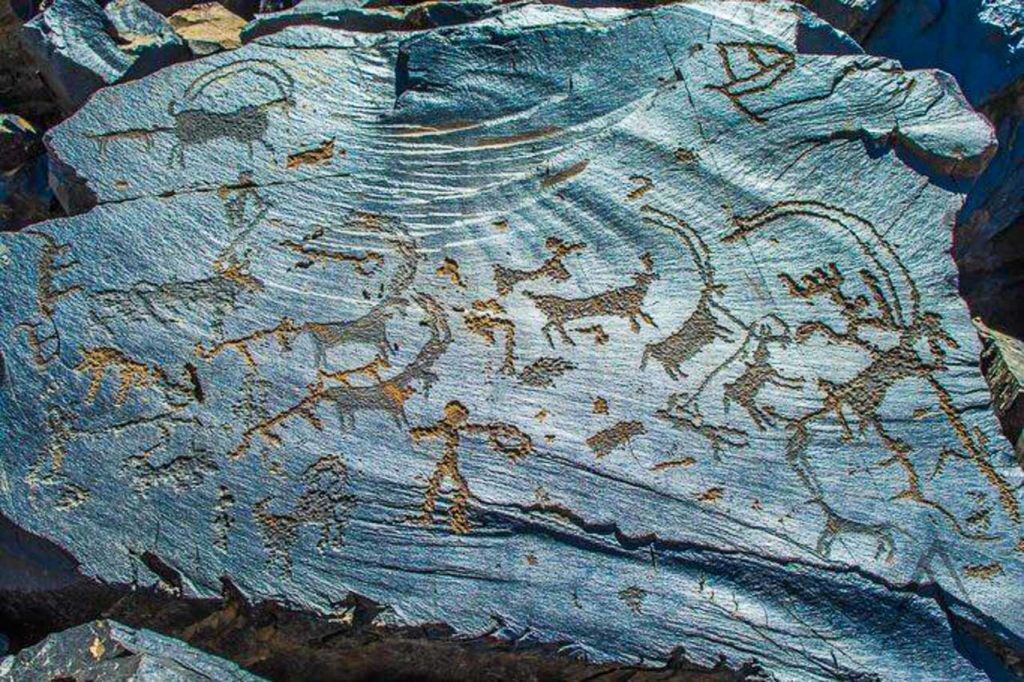

The earliest petroglyphs in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan likely date back to the Bronze Age, between 2000 and 1000 BCE. During this time, people led settled lives, practicing agriculture and animal husbandry, which is reflected in their depictions of bulls, goats, horses, camels, deer, wolves, snakes, carts, plows, and even a solar deity on the rocks.

Two prominent cults of this era were those of the sun and the bull. The bull, representing ferocity and darkness, was often depicted alongside anthropomorphic figures symbolizing the sun. Another significant cult was that of masculinity, portrayed through scenes of sexuality or battle. Key sites from this period include Saimaluu-Tash, Tamgaly, Kulzhabasy, Eshkiolmes, and Akkainar.

The Iron Age succeeded the Bronze Age, spanning from 800 to 300 BCE. Despite continued engagement in animal husbandry, communities became more nomadic during this period. Depictions of bulls, solar figures, carts, and plows diminished, as did excessive portrayals of goats and hunting scenes. Early Iron Age drawings sometimes exhibited hyper-realism, with deer and goats depicted nearly to scale, alongside stylized curves and spirals. Towards the end of the Iron Age, depictions became simplified, focusing solely on goats with minimal lines.

Ancient hunter-gatherer societies relied on goat hunting for sustenance and used them in sacrificial rituals. Some scholars speculate that early humans may have domesticated ibexes, as evidenced by petroglyphs depicting goats alongside dogs. Main petroglyph sites are situated along the northern shore of Lake Issyk-Kul and around the Zhaltyrak-Tash area.

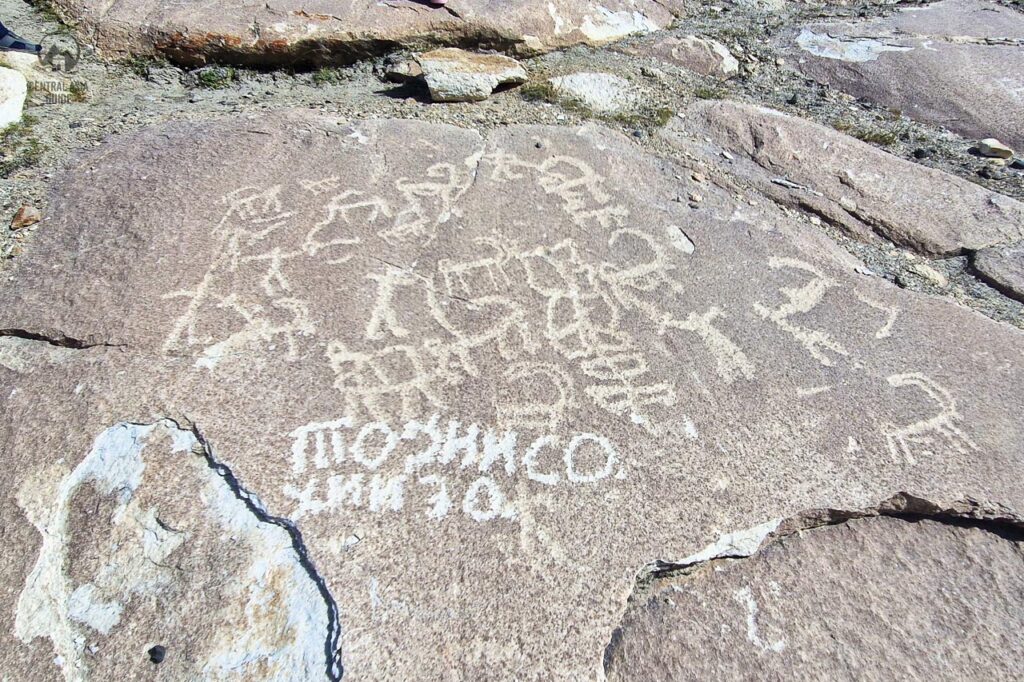

The tradition of petroglyphs experienced a resurgence with the arrival of Turkic peoples during the early Middle Ages (700-1200 CE). These groups refreshed existing petroglyphs, adding depictions of riders carrying banners and caravans of camels. The style during this period favored naturalistic representations. Significant landmarks from this era include Bayet, on the northern shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, and Akkainar.

Petroglyphs in Kazakhstan

In Kazakhstan, the primary petroglyph sites are clustered around Almaty (including Tamgaly, Bayan Zhurek, and Eshkiolmes), Djamboul (Akkainar and Kulzhabasy), and the southern regions such as Arpa-Uzen and especially in Boralday. However, petroglyphs can also be found scattered across other areas, particularly near Baikonur. These sites are nestled in semi-mountainous valleys transitioning into expansive steppes, situated at elevations ranging from 1000 to 1500 meters above sea level.

Petroglyphs in Kyrgyzstan

Rock art in Kyrgyzstan is predominantly found in the regions of Talas (Zhaltyrak-Tash), Naryn, and Jalal-Abad (Saimaluu-Tash), as well as around Lake Issyk-Kul, particularly on its northern shore (Bayet, Ornok, Kara-Oy, and others, including Cholpon-Ata). Despite numerous publications on the petroglyphs of Sulayman-Too in Osh, they hold limited significance due to their sparse quantity and inability to be linked to a specific cultural tradition. Song Kul lake is another great site to hike and search for the abundant petroglyphs in the surrounding hills.

The Saimaluu-Tash area boasts the largest concentration of petroglyphs in Central Asia, comprising approximately 90 000 stones. Dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE (during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages), these ancient drawings provide invaluable insights into the daily lives, beliefs, history, and culture of the region’s ancient hunter-gatherers, pastoralists, and agriculturalists.

Contemporary shepherds in Kyrgyzstan continue the tradition of rock art (often unfortunately). They immortalize their surroundings on stone, whether it be the introduction of automobiles or the reverence for Lenin during the Soviet era. These modern-day depictions are predominantly found along the northern shoreline of Lake Issyk-Kul and in the village of Kulzhabasy.

Petroglyphs in Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, more than 150 sites adorned with rock art have been unearthed, chronicling the country’s history from the Mesolithic era to the late Middle Ages. These sites are primarily concentrated within the Tashkent Oasis, the Fergana Valley, and the Western Tian Shan region. A significant number of petroglyphs are also discovered in Uzbekistan’s mountainous areas, including South Chatkal, Beldersay, along the banks of Chatkal and Ugamsay rivers, in Pschem, the headwaters of the Karakiyasay rivers, Khodjikent, and the Nurata Mountains.

Particularly renowned are the petroglyphs of Sarmysh-Say in the Navoi region. Archaeologists have identified 15 clusters of petroglyphs spread across the Sarmysh-Say territory, representing various periods of ancient and medieval history of the Central Asian peoples.

Petroglyphs in Turkmenistan

Among Turkmenistan’s ancient historical treasures lies the Bezegli Valley, nestled within the Chendir Gorge of the Maktumkul district in Lebap Province. The inscriptions adorning ancient stone statues represent early forms of ideographic writing. Notably, one inscription proclaims, “Ash is the source of prosperity.” These wall inscriptions were initially unearthed in the small Bezegli Valley and are estimated by scholars to date back approximately 14 000 years.

The petroglyphs scattered around Lake Sarykamysh exhibit a rich variety in both theme and artistic style. Dominated by linear-geometric compositions, these artworks also feature depictions of humans and wildlife, offering a glimpse into Turkmenistan’s ancient past. Other petroglyph sites in in Turkmenistan can be found nearby the Ustyurt plateau and in the Chandyr river area in the southwestern part of the country.

Petroglyphs in Tajikistan

The landscape and geographic positioning of Tajikistan reveal three distinct zones where rock art sites are concentrated: the Eastern and Western Pamir (Badakhshan), the Gissar-Alay region, and the Western Fergana (Kurama and Mogoltau mountains).

In terms of the quantity of petroglyphs, Tajikistan’s monuments can be categorized into three groups:

- Sites boasting over 1000 or even several thousand drawings (such as Bybistdara – 1200, Langar – 6000 petroglyphs).

- Locations featuring no more than 100-200 images (like Akjilga, Darshai, Salymulla).

- Monuments adorned with 10-20 petroglyphs or even solitary drawings (for example, Kukhilal, Tamdy, and others).

- The third group of sites predominates numerically. The significant petroglyph sites resemble veritable galleries, with entire compositions etched onto the rugged stone surfaces, showcasing numerous rock drawings.

Here, amidst the rocky cliffs, the aspirations and dreams of people for a brighter future are preserved. These drawings convey profound traditions intertwined with the culture of the inhabitants who have long resided in these lands or transiently passed through them.

Page updated 1.11.2024