Qalas of Karakalpakstan

Fortresses and other sights of Ancient Khorezm

The ruins of more than 300 desert fortresses of ancient Khorezm rest mostly in the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan. The southeast part of the Karakalpakstan deserts are dotted with more than 50 old ruined fortresses, called Kalas also written as Qala translating straight as a fortress. The fortresses go also way beyond this area but it is the most interesting part from the traveller’s perspective as it is easily accessed and near other sights and destinations.

The Kyzylkum Desert was not always so dry before as during the earlier centuries about 2000 years ago this was fertile agricultural land, preserving the stable and centralized kingdom of Khorezm. It may be hard to believe nowadays though that the desert steppes of Khorezm were once a densely populated marshland stalked by tigers, traversed by boats, and inhabited by Messagetae Scythians. The Messagetae, Great Scythian nomads, held power here from the sixth century BC. These horseback archers practiced a form of group marriage and killed off elders to de-burden the tribe. Their finest victory came in 529 BC with the death of the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great.

Thousands of years back the Amu Darya river flowed into the Caspian Sea instead of the Aral Sea. During the millennium BC, it shifted direction and head into the Aral Sea. It then sprayed this region with water and it became fertile and increasingly populated, during the first millennium AD. The largest of the Karakalpakstan fortresses have been built during this era to control the region and protect the agricultural settlements from nomad raids.

Some of the many ruins in ancient Khorezm, current Karakalpakstan may have been fortified residences, other military barracks or something else. However, by the end of the 9th century AD, the Amu Daria changed course again on its way to the Aral Sea, forcing the population to leave some areas for lack of irrigation water. Numerous of fortresses had to be abandoned and the land around them slowly started to turn into a desert.

As the Amu Darya forced its way into the Aral Sea, the region slowly drained and dried. Irrigation canals became fragile desert lifelines controlled by feudal lords, vulnerable to nomadic incursions and tribal war. Whenever irrigation canals were damaged, stranded cities withered and died, leaving skeletons of past glory strewn in the desert like the watermarks of high tide. Khorezm fortresses or Elliq Qala in the Uzbek language have been on the UNESCO tentative list since 2008.

The largest of them served their purpose successfully until the 13th century when Chingis Khan razed and captured the region. The residents of the area were mainly killed or captured, towns destroyed, economy ruined and the fortresses abandoned. During the Soviet times, archaeologists got interested in fortresses, partly excavated and cleared them and the most valuable findings were taken to Russian museums and the ruins were left alone again. During the last 20 years, after the independence of Uzbekistan, the ruins have again gotten some attention and some of them have been even restored.

Anka-Kala / Angka Kala

Anka Qala belongs to the 5th-century fort that later became a 12th-century fortified caravanserai built around a courtyard with a well at its center. The fort is built on a square with double adobe walls, a narrow corridor running between the two. The outside wall, the most important for defense, would originally have been 7-8m high. Also written as Angka Qala is located four kilometers east from Koi Krylgan Kala, northeast from Khiva.

Zhanbas-Kala

Zhanbas-Kala fortress was found in the ancient times of Ancient Khorezm. The fort has been preserved well due to its walls that were densely covered with dunes. The fortress has the shape of a rectangle, the dimensions of which are 200*170 meters. The height of the Zhanbas-Kala walls reaches up to 10 meters, which illustrates the great importance and scale of the structure. It was a military structure with powerful defensive functions. A significant feature of Dzhanbas-Kala fortress architecture is the complete absence of corner towers. It does not only differentiate it from other fortresses of the East but is generally not typical of Eastern architecture. For several centuries, the Dzhanbas-Kala fortress stood on the way of the raids of the nomads, opposing them. However, in the 1st century AD, the attackers, using a ram, managed to break through the wall and get inside. According to the archaeologists, the residents most likely died in that violent battle or were taken into slavery. Since then, over 2000 years, the fortress has gradually been destroyed by rains and winds, and today only the ruins remain of its former greatness.

Dzhanbas Kala is located about 20 km northeast from Anka Kala. Dzhanbas Kala was one of the easternmost fortresses in the Khorezm oasis, standing a few kilometers north of a now dry tributary of the Amu-Darya river that ran south-west toward modern-day Turtkul. It is currently located a few kilometers inside a ring of the desert surrounded by marginal farmland and is only accessible via a sandy, marshy track that runs through irrigated fields.

Ayaz-Kala

The most well-known Qala is the truly remarkable, mud-walled Ayaz Qala, which is actually a complex of three forts about 23km north of Boston (Bustan). Ayaz Qala is perhaps the ‘”must-see” place on every Kyzylkum Desert program. The outer walls, built upon a flat top, have survived since at least the 4th-century BC, and you can clearly see the scale of the site the fort’s footprint was a remarkable 182m by 152m, and even today sections of the wall survive that is 10m high.

Southwest of Ayaz Kala I is a much smaller fortress, the Ayaz Kala II, at the top of a conical hill. 650 meters to the SSE is a large, parallelogram-shaped fortress called Ayaz Kala III in considerably worse repair than the other two. Ayaz Kala I, the most stunning of the three sites, dates back to the 4th century BCE, according to the area’s independence from Achaemenian Persia which ruled the region from the 6th to the 4th centuries BCE. Later, sometime in the 3rd century BCE, the U-shaped bastions were added to the existing walls, providing an extra layer of defense.

Ayaz Kala III was likely built somewhat before Ayaz Kala I in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE. Unlike the hilltop fortress, it formed the walls of a fortified town as it is surrounded by remains of farms, vineyards, and watercourses which today have completely dried up due to the southward shift of the Amu Darya river. Over a thousand years later, sometime in the Afrighid period (late 7th to early 8th centuries) the residents built what is today known as Ayaz Kala II, an oval fortress located atop a conical hill 450 meters to the southeast of Ayaz Kala I.

The fortress was related to a somewhat larger square palace via a long, sloping ramp that lead down from the southwest, providing a ready means of refuge if the palace should be attacked. The palace was destroyed by at least two different fires. Coins dating from the rule of King Bravik of the Afrighid Khorezmian dynasty were located in the rubble.

The Ayaz Qala would once have been a very wealthy place with modern inhabitants. At least ten major buildings have been identified within the complex, and archaeologists have unearthed everything from early wine presses to golden statues. Twelve golden statues were also discovered in the ruins of local ruler Ayaz Khan’s residence, built in the 4th to 3rd centuries BC, and removed to the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. Since “rediscovered” occurred in the 1940s by the Soviet archaeologist S.P. Tolstov.

Kyzyl-Kala

Kyzyl Kala means “Red Fortress”, and it stands a mere 3 kilometers northwest of Toprak-Kala (below). It was possibly built in the 1st to 4th centuries AD and was finally rebuilt in the 12th-13th centuries, just before the Mongol conquests. Although it is described as a fortress, it site may have been primarily used as a garrison post for troops or even as the fortified castle of local strongmen.

The fort is square, covering about 60 meters on each side, composed primarily of unfired bricks and earth infill. Its only gate is located on the southeast side and is accessed by a ramp. The walls rise 13 to 16 meters and wrap around two projecting barbicans on the north and west faces. Many arrow slits and observation points were strung along the walls, though most of these are now hidden by the modern retaining wall that was added to prevent erosion. A second smaller set of walls, located on the top of the fort, afforded additional protection. Innside of the fort is flat and level, covering about 3 000 square meters, but in certain areas holes may be found leading into the ground, the remains of entrances to elaborate underground structures.

Toprak-Kala

The ancient fortress Toprak-Kala had an area of over 120 hectares. The fortress is located 35 km north of Biruniy city and 12 km northwest of Bostun (Boston) village. Scientists believe that in the era of antiquity, Toprak-Kala was once the former capital of Khorezm. It is an excavated town dating back to the 1st to 5th centuries AD and is recognized as the most important monument on Khorezm from the Kushan time.

The Toprak-Kala archaeological complex included several palaces, as well as city residential buildings. The approximate height of the palace was 40 meters. During the excavations, in Toprak-Kala were found richly decorated with monumental paintings and sculptural remains of a palace with 150 halls and rooms and a palace archive of Khorezm rulers. The King’s Palace in the northwestern section of the town was built on an elevated base rising about 15 m above the rest of the town. Three monumental towers, 25 m high, still exist. In front of the palace was the temple area with the holy Zhoroastrian fire.

The town was divided by streets into several districts with blocks of dwellings with 150 to 200 rooms. The Kings’ Hall included an area of 280 square meters. The wall paintings and monumental clay sculptures were the works of a school of arts that could develop a particular Chorezmian style under the influence of Grace-Bactrian art. The rooms of the palace had colorful wall paintings. The fortress is considered as the palace of the shah of Chorezm. In the ruins of Toprak Kale a great number of Kushan and Chorezm coins dating from the 2nd to the 5th cent. and small copper discs with portraits of the rules of Chorezm and written documents on wooden plates or on skins, the most ancient documents in this area, were found.

Koi-Krylgan-Kala

Koy-Kirigan Kala lies approximately 30 kilometres southeast of Toprak Kala, and best approached from the city of Turt Kul. Alike in age to the Djanbas Qala Koy-Kirigan Kala the tastefully named Fort of Dead Rams. It’s perhaps a reference to pre-Islamic sacrifices that took place here. This was a round fortress with a 90m diameter. The inner citadel which is the the oldest part of the site was a royal burial ground. Behind this were rooms for servants and artisans and lastly you reached the outer wall with its nine imposing towers. The Koy-Kirilgan Qala was occupied as late as the 4th century ad.

The fort belongs to 4th century BC to 1st AD forms two unusual and well concentric circles of 42 metres and 87 metres in diameter. The central citadel, originally used as a burial ground for Khorezmian rulers, for cult riles and even astronomical observations, forms a ten-metre high drum covering a central courtyard and six side rooms. Between the inner and outer walls servants’ and artisan rooms spread out radially towards the nine towers of the city defences. The site is best appreciated from the air. Excavations from the site have revealed ossuaries, drinking horns, Scythian headdresses and Khorezmian inscriptions in an Aramaic script and indicate that the site was inhabited from the fourth century BC to the fourth century AD as a dynastic centre.

Kurgashin Kala

Kurgashin Kala is placed 14 kilometers east of the Big Kirkiz Kala fortress and sits at the junction of the Khorezm oasis and the Qizilqum desert. It is the easternmost big fortress in a series running eastward from Ayaz Kala on the edge of a small tributary of the Amu Darya river. It is believed to have protected the northeast corner of the ancient Khorezmian state. As with others in this chain of defenses, the fortress was likely built around the 4th century BCE after the Persian/Achaemenid empire lost control of the region, leaving it in the hands of local powers. It was used at least until the end of the Kushan period. It is in slightly better condition than the Big Kirkiz Kala fortress, suggesting that it may have been repaired and reused afterward, perhaps into the 10th century or later.

The fortress is rectangular with an area of 1.4 hectares and is oriented northwest. The protection includes about a dozen towers, some of which were unusually built in a round shape to increase their overall strength, as it prevented attackers from targeting vulnerable corners. The walls, of double thickness, included a central corridor protected on either side and riddled with a series of embrasures to allow archers a wide range of fire. The main gate stood at the middle of the south wall and included a barbican that forced anyone entering the fort to pass between two sets of walls at right angles to one another, giving the defenders ample opportunity to rain down arrows, rocks, and other weapons on any attacking force.

Big Kirkiz Kala / Big Qırq Qız Qala

Big Kirkiz Kala fortress is located at the border of the Khorezm oasis and the Qizilqum desert. It is one of a series of fortresses running eastward from Ayaz Kala along the edge of the small tributary of the Amu Darya river. The fortress was likely established around the 4th century BCE after the Persian/Achaemenid empire lost the power of the region, leaving it in the hands of local powers. According to the experts, it may have been abandoned afterward, but was reused in the Kushan period (30-375) and again from the 7th or 8th centuries when the area was in the hands of the Afrighids, a Chorasmian Iranian dynasty that survived through the year 995. Today is no more than a ruin, the fortress may have either dropped of population movement driven by environmental changes as well as due to the ravages of various attacks such as those of Genghiz Khan, or a combination of both.

Kaladzhik wellness centre

Kaladzhik is a unique and fascinating destination, it offers a blend of history, culture, and wellness. Kaladzhik dates back to the 4th century BC and was a significan center of ancient Khorezm. The area known for its advanced irrigation systems and agriculture. The ruins of Kaladzhik include the remains of a fortress, a palace, and other structures that reflect the architectural and cultural traditions of the region.

Today, Kaladzhik has become a well known destination for visitors seeking wellness and healing. The destination is home to a number of natural springs and mineral baths, which are believed to have therapeutic properties and are used for a variety of health treatments. The wellness center offers a range of services, including massage, hydrotherapy, and mud therapy, among others. In addition to its historical and wellness offerings, Kaladzhik is also a beautiful natural setting, surrounded by picturesque mountains and landscapes. Visitors can enjoy hiking, birdwatching, and other outdoor activities while exploring the site and its surroundings.

Narindjan Baba complex

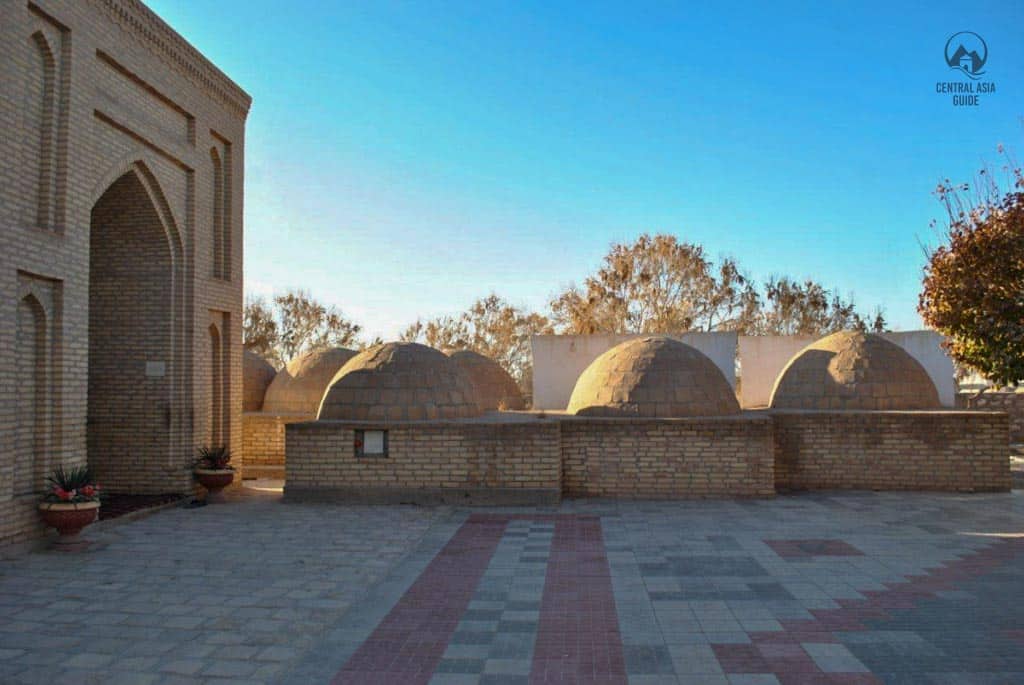

The Narindjan Baba Complex (XIII–XIV centuries A.D.) (or Nurinjan Baba) is one the most sacred and worshipped places in all Karakalpakstan. It is a group of buildings that has been slowly built around a sacred mausoleum with a gravestone of a saint is located in its center. The original tombstones with epitaphs found within the territory of the monument are now kept in the Karakalpakstan State Museum of Regional Studies in Nukus.

Narindjan-baba was discovered in the 13th century by a Muslim leader called Mukhtar Vali, who built the new mausoleum building. A room for pilgrims was added later. This place was often used for Sufi rituals. In the early 1990s the Narindjan-baba Complex was restorated and its gravestone decorated with marble.

Yakke Parsan

Yakke Parsan stands as a fortified manor house dating back to the VI-VIII centuries of the Afrighid era. The remnants of this structure represent a classical Khorezmian castle from the pre-Islamic era, serving as the residence of a feudal lord.

In the initial half of the first millennium AD, a new class of feudal landowners emerged, descending from ancient nobility, senior courtiers, or those honored for faithful military service. Many resided in small square-shaped forts, known as residential towers or donjons, surrounded by defensive walls.

The building stood proudly in the midst of a vast rectangular courtyard, enclosed by double walls adorned with oval projecting towers. Two imposing towers in the center of the southwest wall safeguarded the gates, perfectly aligned with the castle’s portal and hall. An additional double wall surrounded the estate, situated 9 meters away from the first. A continuous strip of residential buildings enveloped the courtyard’s perimeter—connected cells of peasant dwellings, separated by parallel walls. These structures, of equal depth on every side, left only a narrow passage open at the castle’s southeast base, nearly eradicated. The central residential tower spanned approximately 20 by 20 square meters, featuring a central room with an arched dome. The doors led to two smaller vestibules, each housing several rooms.

See more in Karakalpakstan

Page updated 6.3.2023